Science of Language Learning - Zipf's Law

I’ve decided to start a series of short blog posts where I’ll be exploring some of the concepts and ideas behind modern language learning that I find interesting and important. The series will be called the ‘Science of Language Learning’ and will touch on things like frequency lists, spaced repetition and word coverage, among other things.

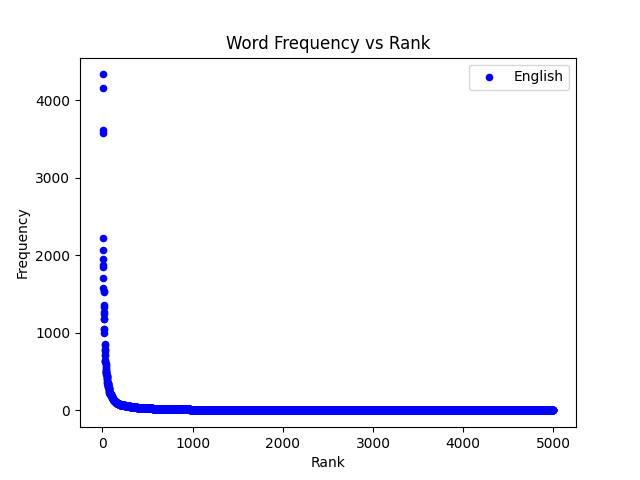

For the first post in this series I wanted to cover Zipf’s law. Zipf’s law, in the context of natural language, describes the relationship between how often words occur, and their ‘rank’ relative to other words in the text. It’s probably best to explain it with a graph.

The above graph plots the number of times each word occurs in the English novel “Pride and Prejudice". In this graph, each point is a unique word that occurred in the novel. Now if you squint your eyes and look at the first four points near the top left, you’ll notice that these four words occur disproportionately more often than the other words. These points represent the words ‘the’, ‘to, ‘of’ and ‘and’ which are the four most common words in the book. Other common words in the book are words like ‘her’, ‘she’, ‘be’, ‘in’, and ‘what’, but after those first couple of extremely common words, there’s a steep drop. The rest of the words like ‘concise’, ‘stubborn’, ‘harmony’ also occur in the book, but are far less frequent. Those words can be seen on the bottom right of the graph.

What’s going on here is that there’s a small number of words that are very common in the text, but also a large number of words that are relatively uncommon. What’s so interesting about this phenomenon is that it’s not just unique to English or Pride and Prejudice. This same phenomenon occurs in every language for any sufficiently large body of text.

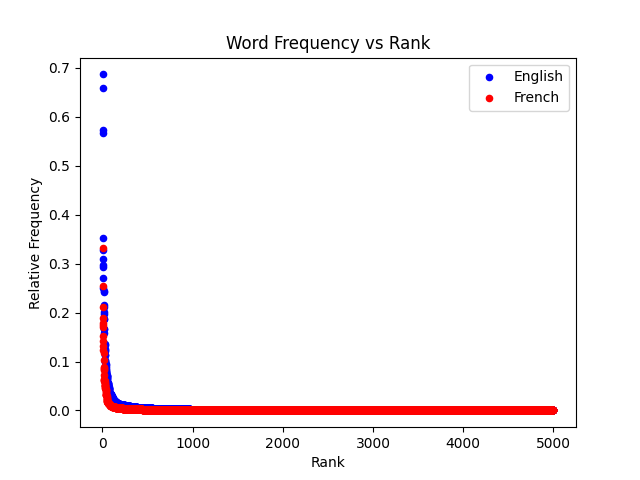

Here’s the same analysis, but in French with the book “Madame Bovary”.

As can be seen in the graph above, we get the same-shaped curve. Even though the languages and books were different, the behavior was the same.

In French, the common words are also very similar. Among some of the most common words, we find ‘de’ (of), ‘je’ (I), ‘et’ (and), ‘elle’ (her) which are short, functional words like what we see in English. In general, the most common words in each language tend to be short and functional.

--

Zipf’s law is what’s known as a power law distribution, which you may have heard of before. Power laws generally describe highly unequal phenomena, like wealth distribution (a small number of rich people have a disproportionate amount of the money) or city populations (there are a small number of huge cities with lots of people vs. a large number of small towns where there’s few people).

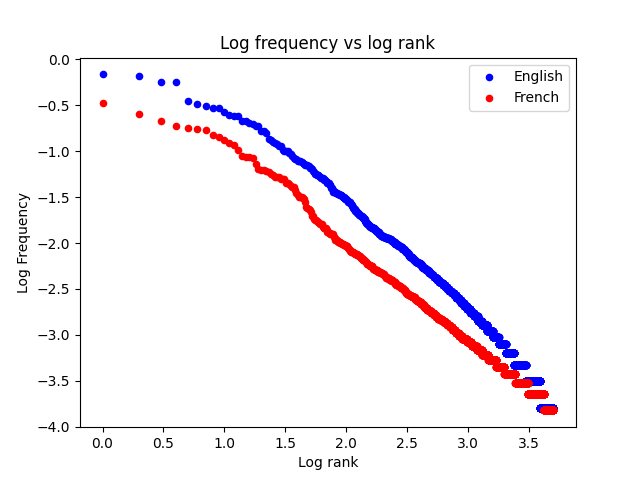

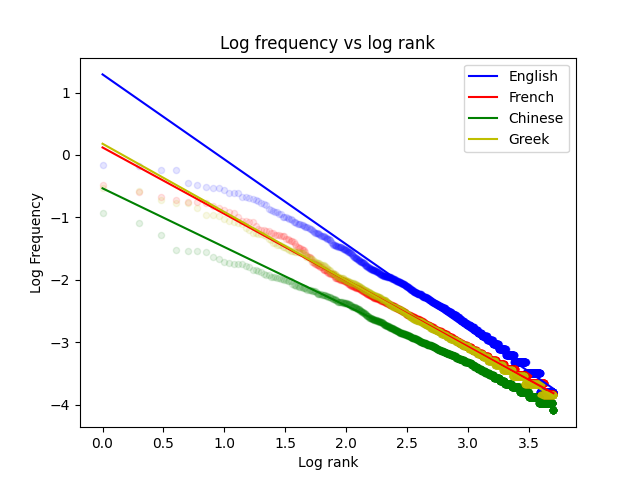

One cool thing about power laws is that there’s a much nicer way to visualize them using a log-log plot.

If you’re not familiar with what a log-log plot is, don’t worry about it, it’s just another way to visualize power law data, but in a nicer way.

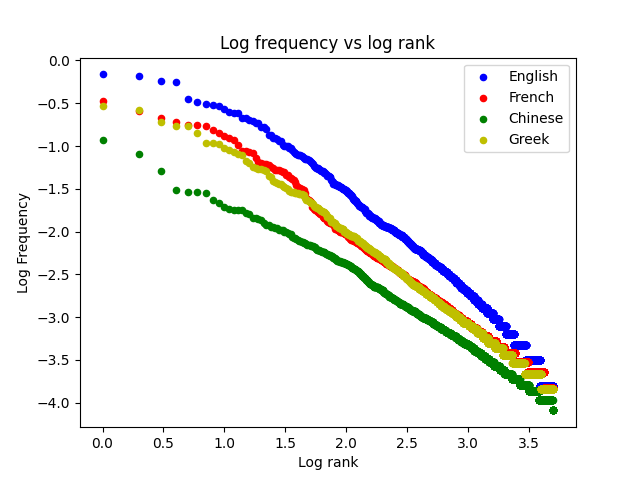

Here, we have the log-log plot for four different languages from four different books:

Once again, we can see that each language exhibits the same behavior.

In fact, while you’re technically not supposed to do this, you can actually model these curves quite accurately with straight lines using a linear regression model.

What we can see above is that the Zipf phenomenon is actually pretty easy to model and make predictions with, which can be quite useful for research purposes.

--

But how is any of this relevant to language learning?

Zipf’s law actually has a ton of implications for language learning, but here I’ll only touch on the two implications that I find the most interesting.

The first implication is that some words are much more useful than others. If you’re just starting out learning English, it’s probably better to learn words like ‘go’, ‘him’, and ‘eat’ before words like ‘generalize’, ‘vegetation’ or ‘bombastic’.

This realization has led some language learners to create ‘frequency lists’ of each language’s most common words. Some believe that it’s a good idea to study vocabulary according to a frequency list because it allows you to focus on the words that are used most often while not wasting too much time on words that are only used rarely. And while not all language learners agree that you should use a frequency list, they are becoming more popular and have certainly helped a lot of people.

The second interesting implication of Zipf’s law is that it also roughly describes the order in which learners naturally tend to acquire vocabulary.

Because the most common words are repeated so often, they also tend to get acquired first by new learners while the more uncommon words tend to get acquired later. It’s interesting that, whether or not a learner decides to use a frequency list, they will still end up acquiring the most commonly used words first, anyways.

As a consequence, one rough measure for judging a language learner’s level in the language is to simply figure out how many rare words they know. A learner who lacks knowledge of a language’s most common words is clearly a beginner, but a learner who knows thousands of rare words is usually much more advanced.

--

There are many more concepts that are closely related to Zipf’s law that have interesting implications to language learning, but I think I’ll stop myself here for today. I do plan on covering related topics such as Heap’s Law, word coverage and hapax legomena, but those will be for another post. In summary, Zipf’s law is a power law that describes the relationship between word frequency and rank in every human language and we can use this curve to help us better understand how to acquire vocabulary in a foreign language.